Day 1 of Virtually@RYDE and a much quieter place than last Friday when emotions ran high and I was able to raise a glass of bubbly with our Upper Sixth formers before a mass school House Run and TikTok dance.

Now pupils and staff are busy in lessons and lunchtime activities have been advertised including an electric guitar workout, pet club and beginners tango.

Friday was a sobering day for us and our final assembly in the senior school gave me the time to thank all those staff who have worked so tirelessly in all areas of the School over the last couple of weeks to prepare us for this day.

Below is an extract from that Speech, which ended with Kipling’s ‘If’

“I have appreciated more than ever over this last week all those at Ryde who make this such a special place ….The creativity, dedication, flexibility and empathy they have shown over these last few days has been extraordinary. We haven’t just made remote teaching work, it has worked spectacularly well – so even now many of you are beaming in… Next week you will all have three days of remote teaching. After that we will have an extended Easter holiday and we will come back, either remotely or reunited in this place, to study as a community across not just our Island but the world. A special welcome to any of our boarders beaming in now from distant parts, and the very best of wishes to those of you about to head off. There will be challenges for all of us, but it will also be exhilarating. We as teachers will be trying to catch up with a world you are far more familiar with. And it won’t just be lessons; there will be clubs and activities, challenges and morning work outs. We will have some fun.

That doesn’t mean that I am not aware of how unsettling a time this is and I speak particularly to those of you in the Upper Sixth. We cannot yet be certain what the immediate future brings, but I promise to you that I will work hard, as will our magnificent team of Sixth Form tutors led by Mr Windsor, to make sure you can move on confidently when the time comes. We cannot know exactly what next term will bring and it may vary depending on whether you are studying for IB or A level. We will support you as individuals, whether that means facilitating an extra term or year, supporting you to an early exam or advising you on the next step. We will also do all we can to mark your achievements, both individual and collective, over the entire span of your Ryde career, some of which have lasted 16 years. There will be a Leavers’ Dinner and a Year 11 Prom.

I have been very impressed with the level of commitment shown by Year 11 and Upper Sixth this year. Your mock exam results show that you are on course for some of the best results for some time and some of you may be thinking all you have worked for has been in vain. Your teachers might sense that too. But that is not the case. Ryde is not a school that has ever said education is purely, even primarily, about exam results. It is about education, and I feel proud to have worked with my group of 7 politics students this year, and my Global Perspectives class last term, in developing higher order thinking about political ideas that matter. Whether you do the exam or not, you now know and understand a lot more than you did at the start of the year. You will be no less educated because you haven’t been assessed for six hours on two years’ work.

You and your families know that education, true education, is about character, about skills and habits, values and action. It’s about the person you become because of the people you meet, the decisions you take, the friendships you form. The memories we create together. Everything you have done and achieved here at Ryde has educated you and others and will continue to do so. Ask your parents how many know what subjects their friends studied at school, never mind what grades they got. Your education is so much more than a set of exam results. Remember that.

As the great historian Geoffrey Elton said,’ the future is dark, the present burdensome’. We live in turbulent times that will get more difficult before they get better. A lot of people talk about unprecedented times. Unpredictable is probably a better word. You only have to walk each day into the McIsaac Building and pass the memorial walls for Bembridge, Upper Chine and Ryde to know that previous generations have faced greater challenges still. Some of those most vulnerable in our current crisis are those who made the call to service when our nation was most under threat. And at your age. But these are challenging times and for my generation and yours they are unprecedented. There will come a time when worrying about a GCSE grade in History will look trivial compared to the experience of living through it.

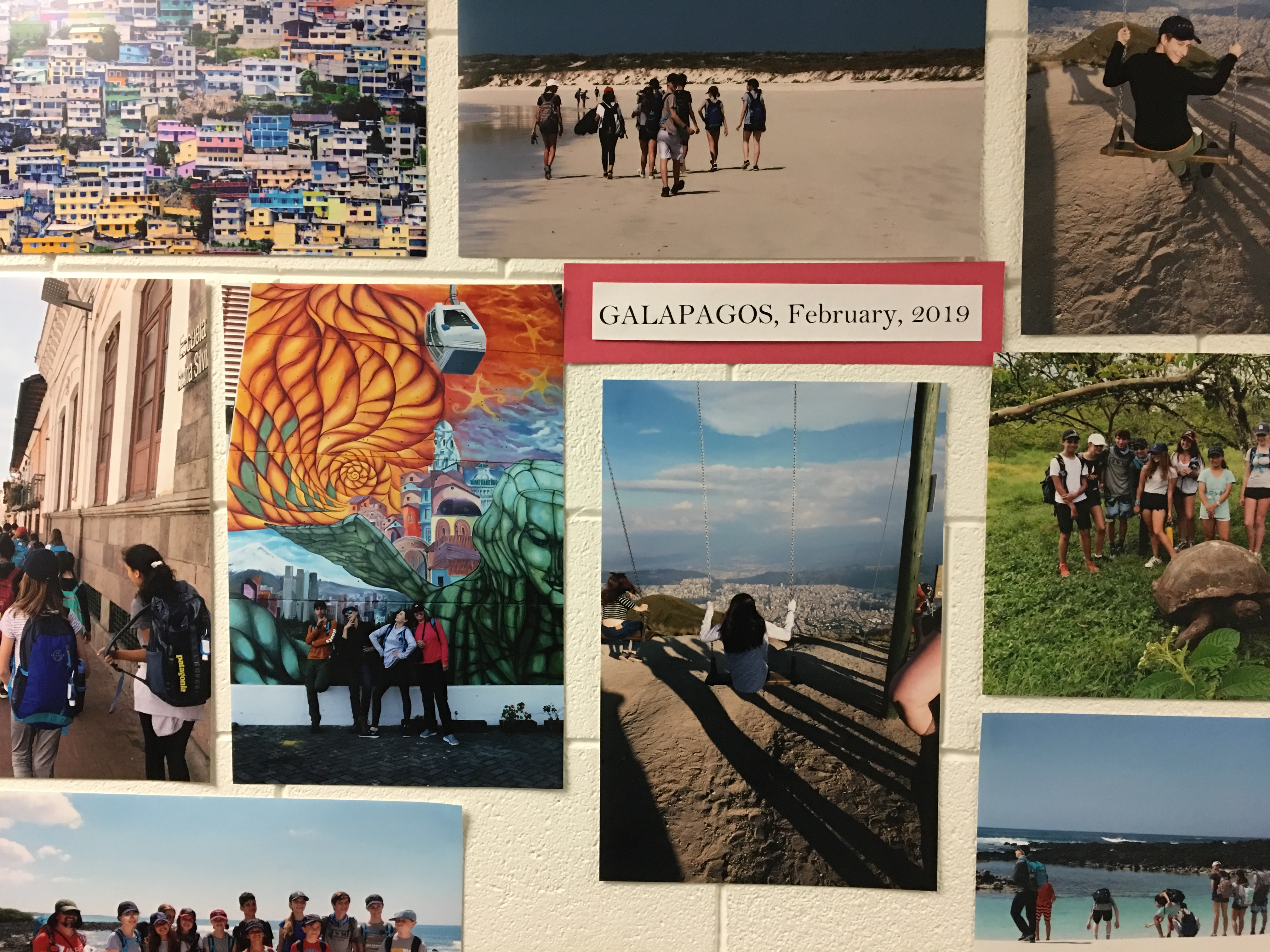

Our Island School with a Global Outlook has enjoyed much of what globalisation has to offer, we are about to discover there is a downside, but it is a downside that cannot compete with the joy, the cultural enrichment and personal development that comes from being a global citizen. The upside will soon return. But, maybe after this we will think more about the fragility of our planet, of the importance of companionship. Dare we hope we can become more aware of those in our community who we sometimes forget – the elderly, the lonely, the vulnerable? Will we learn to appreciate more those things that we might be missing over the next few weeks – sport, drama, music, adventure – and get more out of them in the future.

I want to finish by thanking all of you for the spirit you have shown and I wish you and all your families the very best for the next few weeks. Stay safe. Be sensible. Look after yourself and your families. Remember your parents will be under pressure too, and they will be worried for you and their own parents. Think about those in your neighbourhood whom you can help – with shopping or gardening, or maybe just messaging and giving a wave.

It is exactly one hundred years ago today that Roy McIsaac, Headmaster from 1953 to 1966 and son of our founders William and Constance McIsaac, was born. Next year we will all gather as Ryde School with Upper Chine, celebrating our hundredth year. Make sure, when we do, and we invoke the spirit of Ut Prosim, that we can do so with anecdotes to share and stories to tell of how we were of service in the crazy Coronavirus Crisis of 2020 and make sure we were not lacking in the fight.“

God bless you all. Ut Prosim.

Mark Waldron, 23rd March 2020, Day 1 of Virtually@RYDE